Combinatory Categorial Grammar (CCG) is one of the many, many (far too many) syntactic formalisms posited by linguists in the Chomskyian era. CCG has been outlined in work by Mark Steedman, the most recent guide being his 2001 book which I have to read for a class.

Unlike most other syntactic theories, I find the mechanics of CCG very elegant. There is no difference between the distributional categorisation of a lexeme and the argument structure that it has; both are neatly contained in the CCG type system, and the connections to type theory just work out very nicely (with the caveat that this is in my limited understanding of type theory).

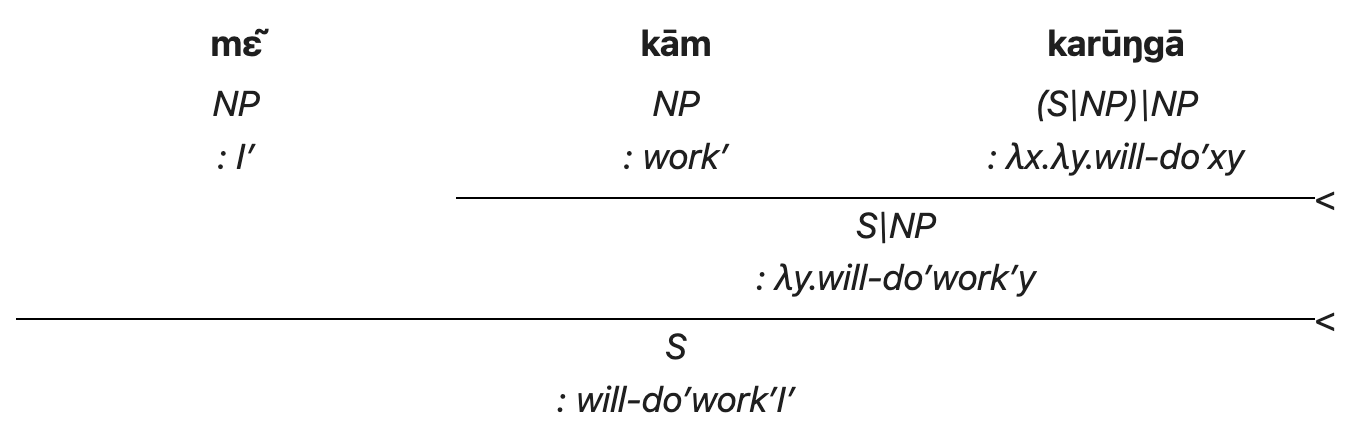

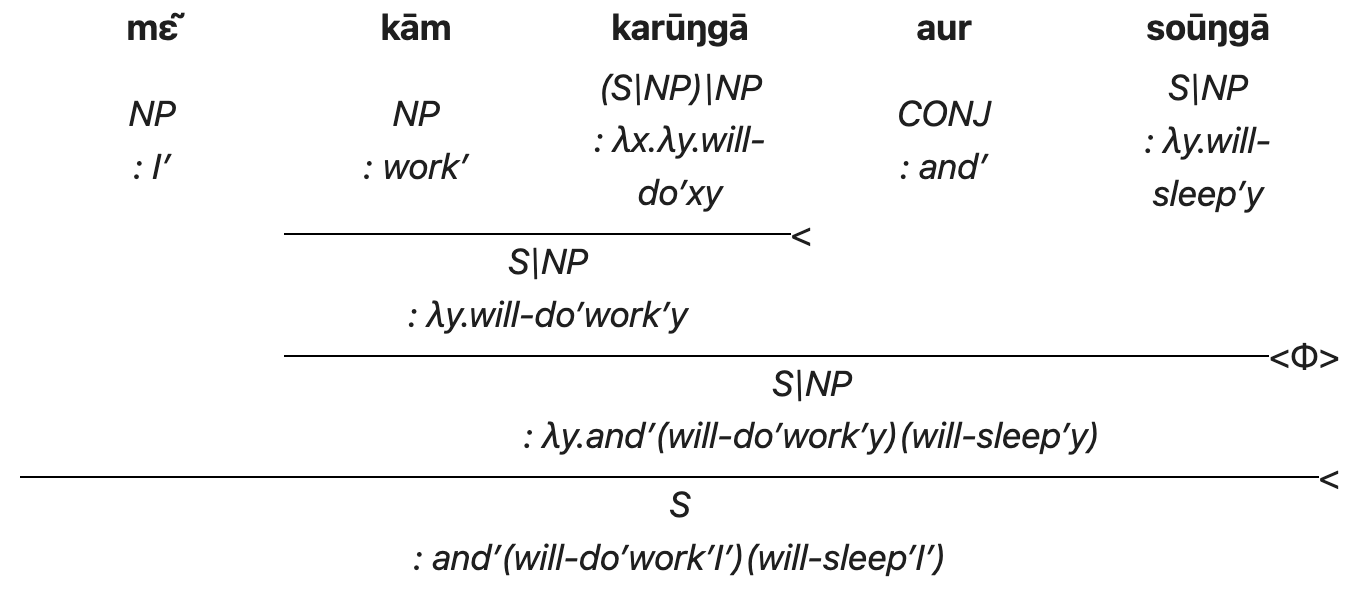

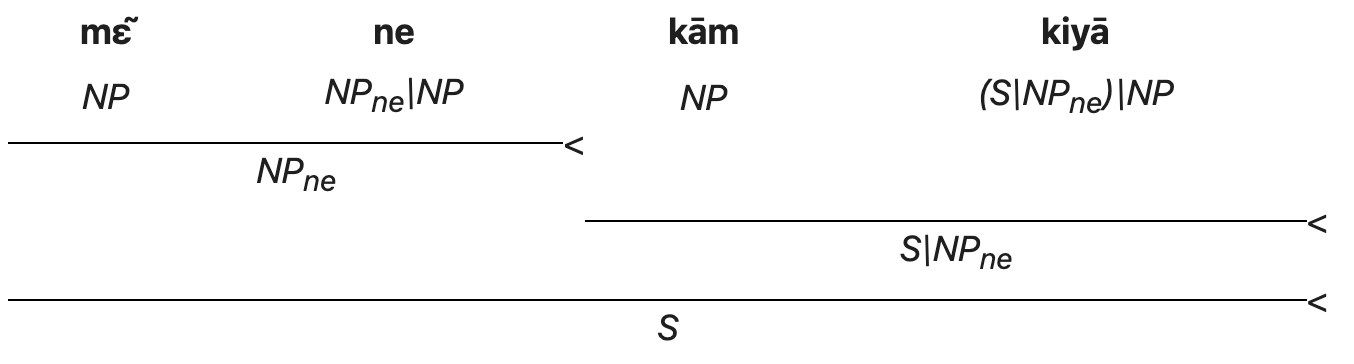

Naturally, I was thinking about how CCG would be applied to Hindi syntax. This isn’t anything novel (see this 2017 paper on exactly that) but for my own edification I wanted to see how flexible CCG is across languages. Here’s CCG analysis of some simply clauses in Hindi; as you can see, all the derivations proceed backwards, which makes sense since Hindi is pretty left-branching.

So, those were pretty straightforward; note that I also included a weak functional representation of the semantics in the same lambda calculus of Steedman. You can see that the familiar (S\NP)/NP of English is replaced with (S\NP)\NP, corresponding to SOV structure in Hindi (both verbal arguments are to the left). I do wonder how a language where the object is further than the subject would work though.

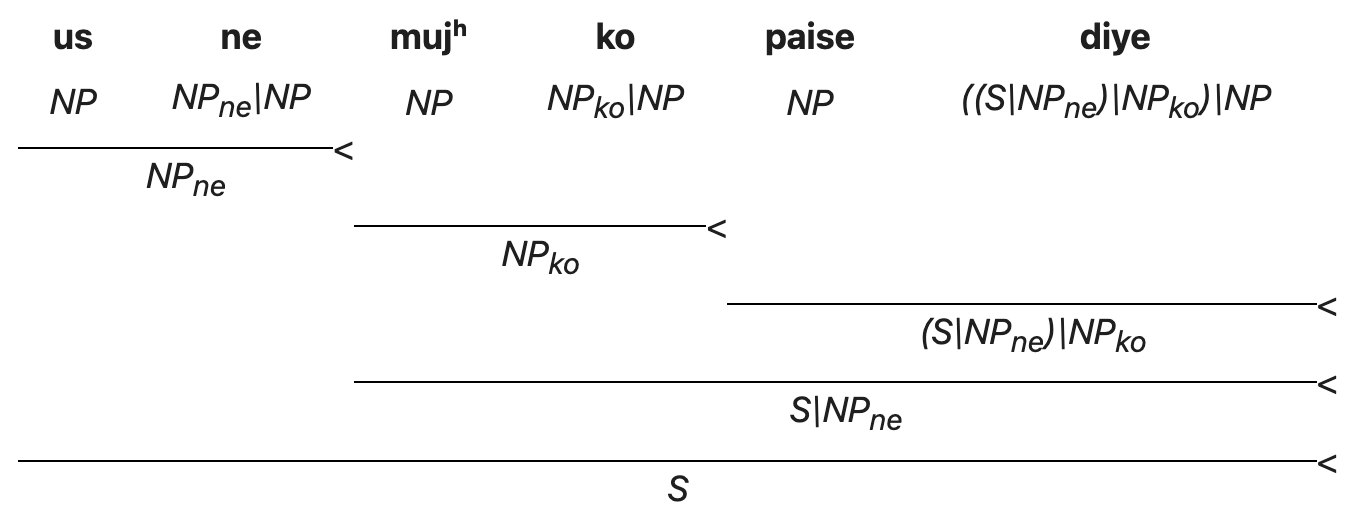

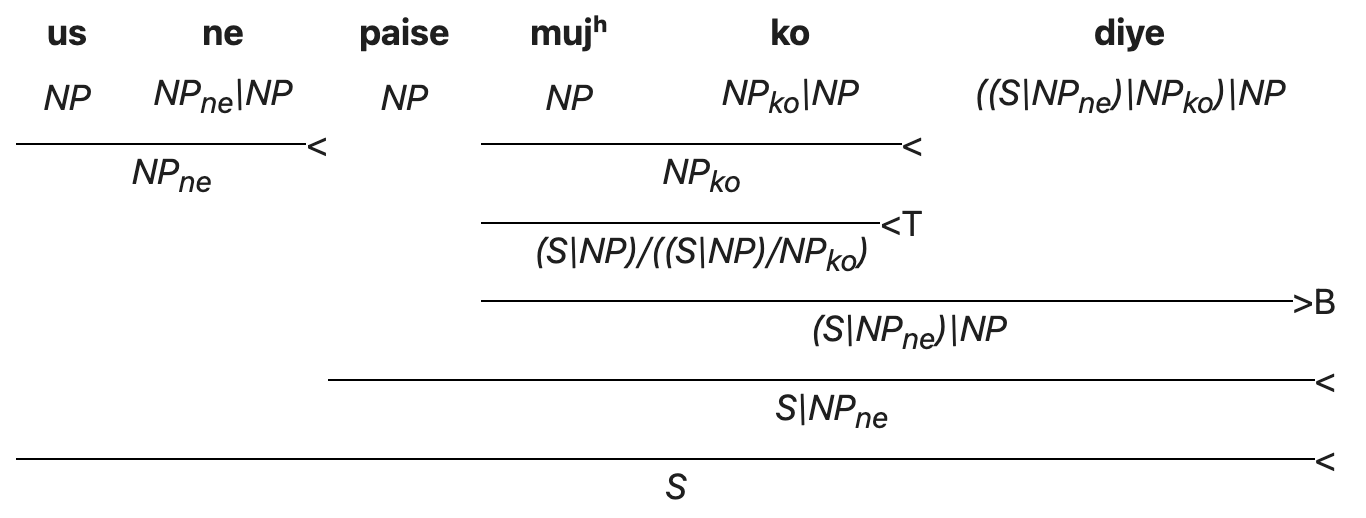

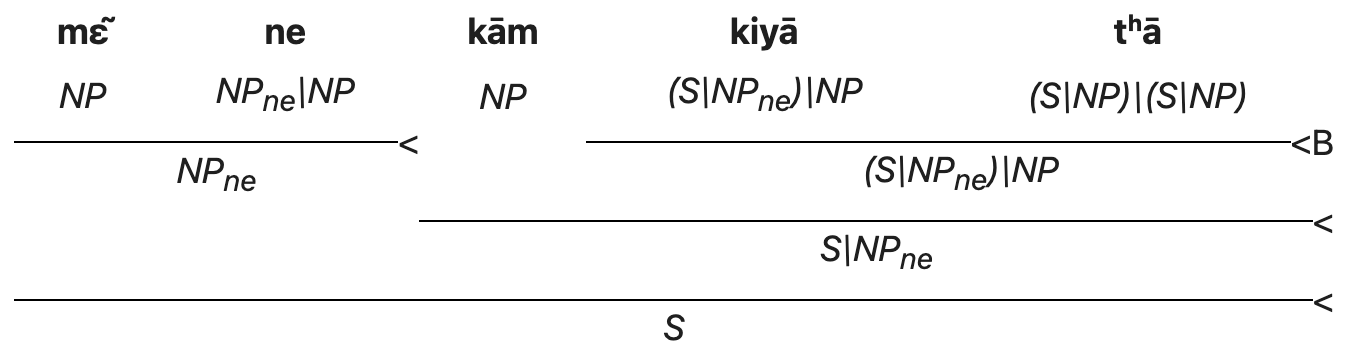

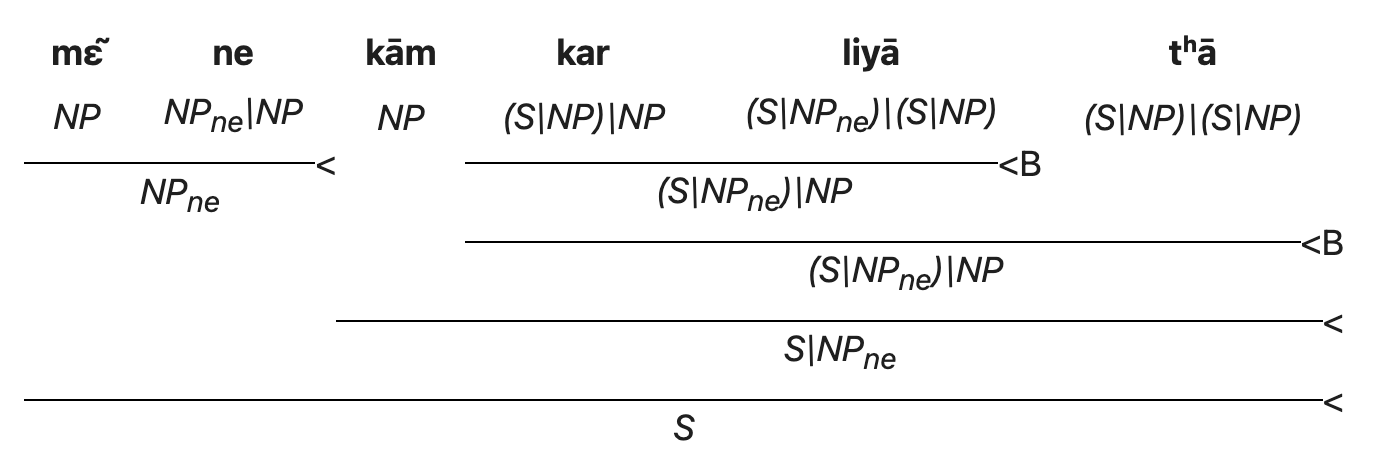

Here’s a more complex clause, with a ditransitive verb as well as another example with non-canonical word ordering. The preferred way to analyse non-SOV orderings (which are canonical in Hindi) is with type-raising and then forward composition (a rare rightwards derivation). I am reminded of how CCG handles relative clauses in English, which have screwed-up word order due to an argument being moved out of the clause.

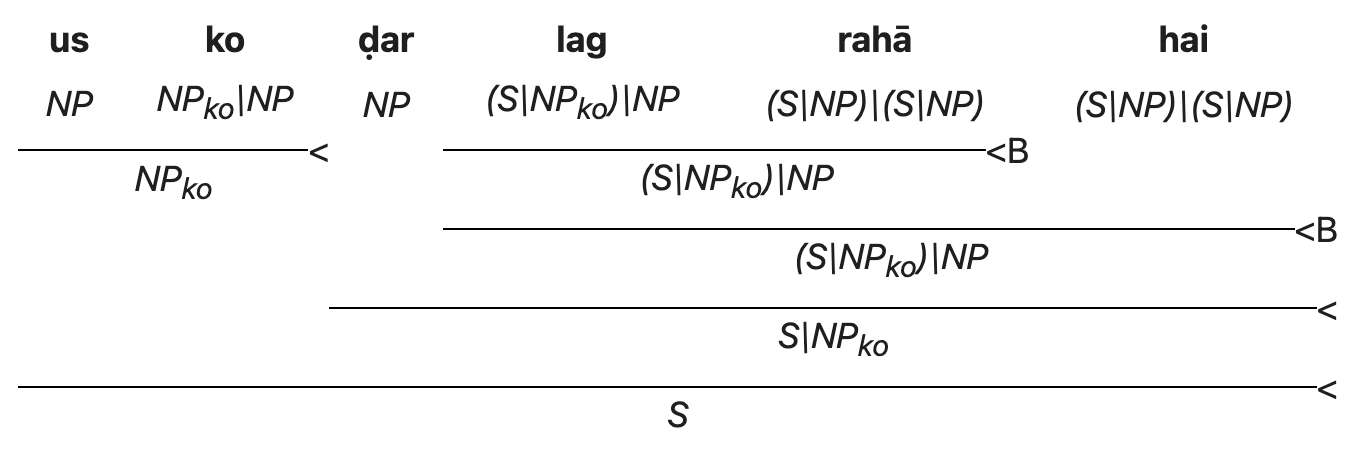

One thing I would like to explore is ergativity. Ergativity has been studied to death by Hindi linguists, unfortunately. But I like how you can easily express the verbal ergative agreement using a feature on the subject, which even works well where a serial verb overrides the agreement of a main verb. Also, check out all the nice left derivations!

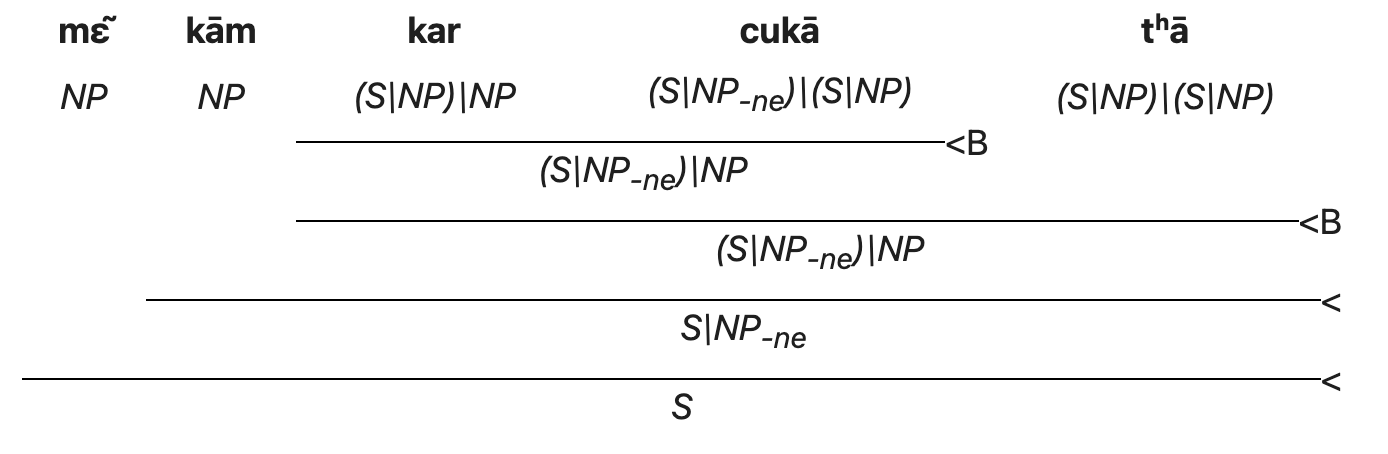

Here’s how lenā and cuknā are handled as serial verbs; the former takes the ergative and the latter does not. The backward composition operation overrides the unspecified subject type of the bare verb kar.

Dative subjects: