Aryaman Arora » Blog » Bhāṣācitra

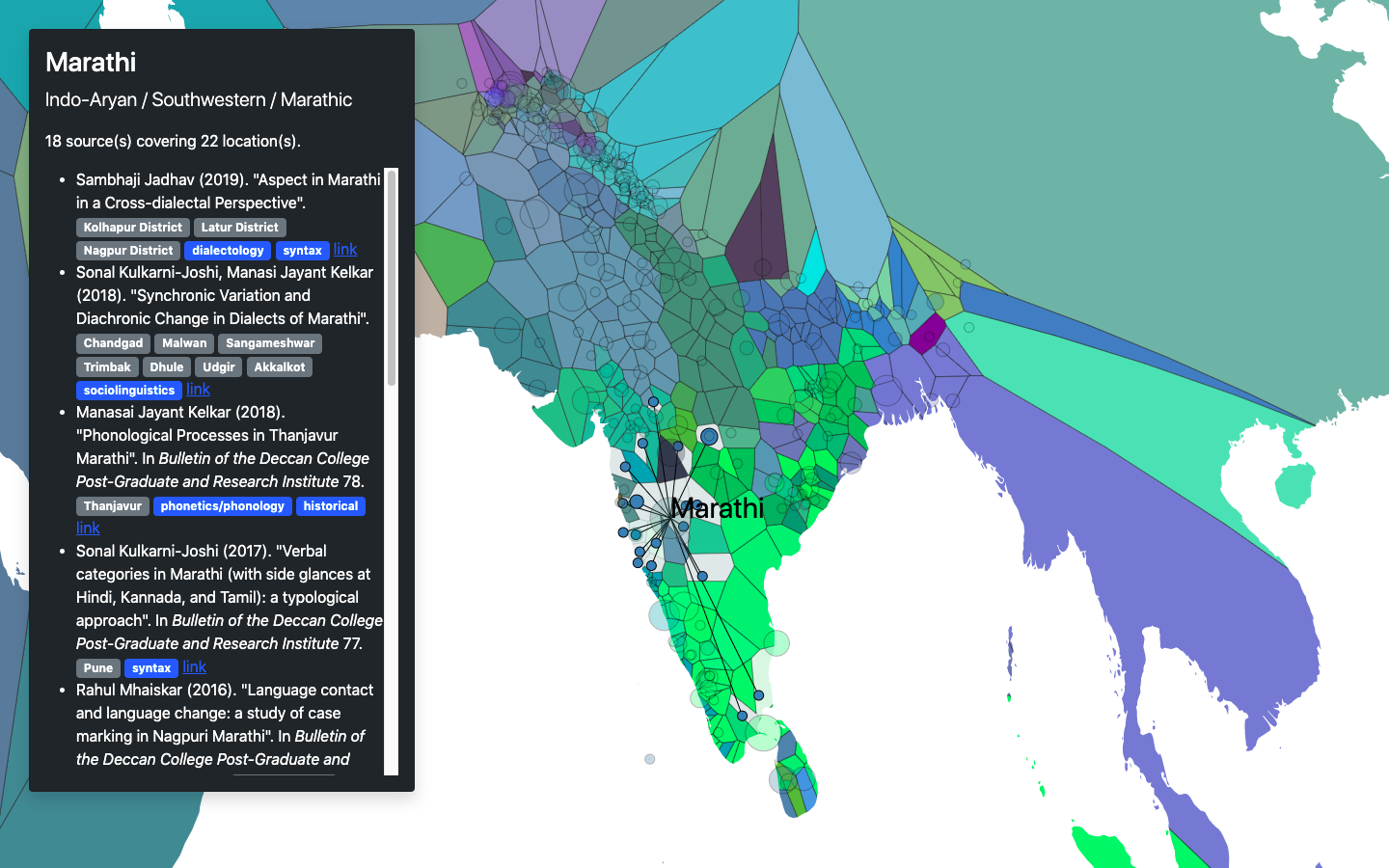

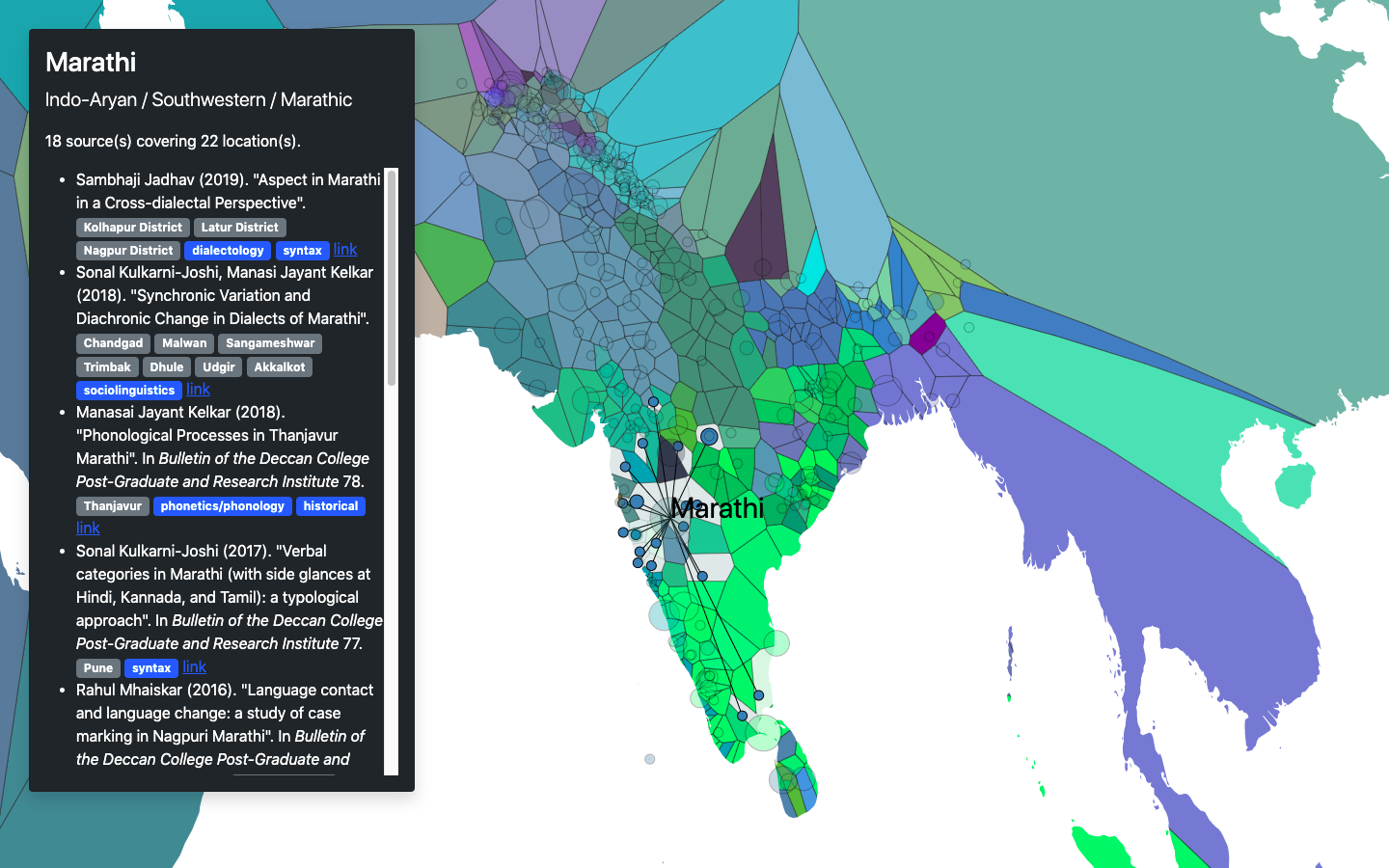

Recently, I’ve been working on mapping the languages of South Asia by

organising the scholarly work that has been done on individual

varieties—this means sociolinguistic surveys, grammatical descriptions

of standardised dialects, and any other fieldwork-based study of

language. At first the goal was to organise the works that I read and

reference in a way that is (1) useful to others, and (2) easy to browse

through, but I came to realise that it can be useful beyond that, for

more general-purpose language mapping. By plotting the locations of

individual studies and dividing the map into zones around each point

through some sort of nearest-neighbour interpolation

So far, I’ve only tried a geographic version of the

Voronoi algorithm because it is easy to implement in D3.js with the

d3-geo-voronoi library.

we can create language regions, which approximate the geographical spread

of languages. The result of this is Bhāṣācitra.

You can hover to see zones and click on dots to see sublocations and references. The colour scheme is automatically generated (string to hex hashing function) so it’s a little wonky. On the tech side, this was all done through some JSON files and D3.js—I do not have the money to host a webapp for the foreseeable future and I don’t actually like coding web stuff! The data collection that went into the map was not a solitary effort: Adam Farris, Samopriya Basu, and Gopalakrishnan Ramamurthy provided a lot of the sources for Insular IA, Dardic and Pahari, and Dravidian (respectively). Some highlights:

The obvious issue in this approach is that linguistic work is not being done at a sufficiently fine level in South Asia to make really small zones/a very fine-grained distribution of points. (That’s not to say the there is any lack of linguistic work being done in South Asia—one of the things I’ve realised in mapping all these references is that there is plenty of work, it’s just hidden away in unpublished theses that we can only now access through Shodhganga, and papers in obscure non-digitised journals.)

The kind of data this map ideally would be built on can only really be collected in expansive dialect surveys, which are rare in South Asia. The only recent examples that come to mind are the SIL sociolinguistic surveys, which have only focused on a few regions of South Asia, and the Survey of the Dialects of the Marathi Language.

Still, it’s a useful gathering of sources that I don’t think has been done for this important linguistic zone. One of the uses may be mapping areal features: here’s a prototype looking at some phonological features: the presence of contrastive breathy-voicing and historical post-nasal voicing. Other things that may be interesting to map:

There has been similar work on other regions, like Henrik Liljegren’s work on mapping and analysing the areal features and typology of Hindukush-Karakoram region languages and Erik Anonby and Mortaza Taheri-Ardali’s Atlas of the Languages of Iran mapping language distributions at the village level.

One of the data integrations I have thought of is extracting data from an etymological dictionary (like Turner’s Comparative Dictionary of the Indo-Aryan Languages), and, at least for phonological features, mapping out the likelihoods of individual sound changes or even a regex-based querying system for sound change. The initial extraction of data from CDIAL wasn’t so hard (it’s already digitised), but now I’m stuck on finding or making a good alignment algorithm, especially to cover things like metathesis. The usual dynamic-programming edit-distance algorithms can’t handle that very well; plus, we need to make decisions about how to measure phoneme distance (e.g. what are the distances between /pʰ p b/? /pʰ~p/ = /p~b/ or not?). I’m sure there’s work on this, but I’m totally new to it so these are just some musings. Another approach that comes to mind is something neural, sort of like the LSTM encoder-decoder in Cathcart and Rama (2020), but for alignment instead of prediction. One idea is to train contextual phoneme embeddings, and then run something like Sabet et al. (2020)’s Simalign algorithm. Maybe pretrain on manual alignments of tricky cases first.

Anyways, there’s plenty of neat stuff to be done in this system. It’s a fun side project for now (apparently, I like making datasets), maybe will result in something publishable in a more formal format someday.